Stages: the Framework for Assessing the Risk and Security of an Ethereum Rollups.

We use Arbitrum or Optimism instead of Ethereum because transactions on the latter are too expensive, but do we know what we are doing and what we are getting into? L2 solutions, such as Optimistic Rollups and ZK-Rollups, aim to improve the scalability of Ethereum by reducing the load on the core network (Layer 1). But the question is, how secure are they?

When we talk about security in an L2 what do we actually mean?

Security in Layer 2 (L2) solutions on Ethereum is primarily about protecting user funds and transaction integrity. It is essential to ensure that bridges, which allow the transfer of assets between Layer 1 and Layer 2 and vice versa, are secure to prevent theft. In essence, how decentralized are they really and how much does the user’s willingness to withdraw their funds not clash with the discretion of those operating the rollup or other L2 protocol?

Brief description of Rollup architecture: terms and functions of various components.

Let’s take a step back, what are rollups? Simply put, they are solutions that “compress” user transactions within batches. Instead of having N user transactions in chains, these are precisely included in a batch and each batch is then “inserted” into the main chain.

This means that the N transactions above eventually result in one transaction on the main chain. That’s sound convenient, doesn’t it?

Enter and Exit the Rollup. That’s important.

Here’s the kicker, eventually when we want to use a rollup at least one transaction in L1 that makes our funds available to the rollup in L2 we have to do it. And vice versa when we have decided that we no longer need the rollup we must be able to get our funds out of L2 to L1 without others having to object, unless we are trying to commit fraud, of course. On the anti-scam protocol we will come back to it shortly.

In fact at the extreme the same things that an L2 does could be accomplished by a centralized entity that receives the funds from Alice, Bob and everyone else and then when they want to transact with each other holds the accounts on a centralized ledger.Like a payment institution would do if it were fiat money.

But here’s the point. An L2 must (or should) replace the “centralized” execution part with a protocol that does not require an individual to do it. But is that really the case?

What STAGES is for.

Stages is a framework that can help developers, investors, and users make informed choices when considering the use of a specific rollup.

The “STAGES” framework for assessing the maturity of rollups relies on a rating scale of 0 to 2 to determine the state of development and decentralization of various rollups on Ethereum. Each “stage” represents a level of maturity:

- Stage 0: At this stage, rollups are in the most basic stage of development. They are mostly in the testing phase or have just started operating under controlled or limited conditions.

- Stage 1: Rollups at this level are more advanced than Stage 0. They have demonstrated some degree of functionality and reliability, but may not yet have implemented all the features necessary for fully secure and decentralized operation.

- Stage 2: This is the highest level, where rollups have fully realized their technical and operational features, offering high security, scalability, and decentralization.

The STAGES framework helps developers, investors and users understand the development level of a rollup, facilitating more informed decisions about adopting or investing in these technologies.

How to use the framework to do our evaluations.

TL;DR Basically: stage 0 is a rollup totally in the hands of operators. stage 1 is a rollup partially in the hands of operators and partially autonomous stage 2 is totally autonomous and based on smart contracts.

Going into more detail, here are the various requirements

Stage 0

This stage focuses on elementary validation and transparency of the rollup:

- Identification as a Rollup: Checks if the project is self-identifying as a rollup.

- Publication of L2 state roots to L1: Ensures that L2 state roots are posted to the Level 1 blockchain.

- Data Availability on L1: Checks whether the project provides data availability on the level 1 blockchain. Although zk-rollups would theoretically not need to show data, only proofs, to prove the correctness of transactions, it remains necessary to allow access to transaction data even for the purpose of reconstructing the entire state.

- Source code accessibility: Assesses whether software capable of reconstructing rollup state is available as open source.

Stage 1

This stage verifies the robustness of the proof system and the interaction of external actors:

- Use of an appropriate proof system: Confirms the use of an appropriate proof system for rollup.

- Submission of fraud proof by external actors: Verifies the ability of at least 5 external actors to submit a fraud proof.

- User exit without operator coordination: Checks whether users can exit the system without operator coordination.

- User Exit Time: Ensures that users have at least 7 days to exit in case of unwanted updates.

- Security Council Configuration: Examines whether the Security Council is set up correctly.

Stage 2

The final stage evaluates the full automation and decentralization of the proof system:

- Permissionless fraud proof system: Evaluates whether the fraud proof system is permissionless, allowing anyone to participate.

- Extended exit period for users: Confirms that users have at least 30 days to exit in case of unwanted updates.

- Security Council Limitations: Ensures that the Security Council can only act in response to errors detected on the blockchain.

For more details on each requirement and insights into their impact and application, you can check out the original article on Medium at this link.

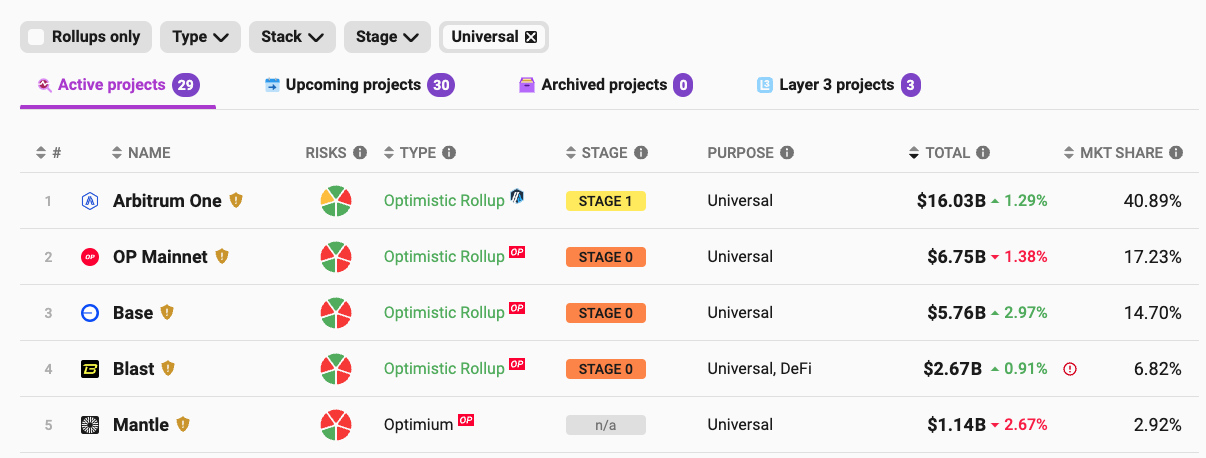

How safe are the major Rollups we use?

This is an interesting question that we can try to answer thanks to the analysis provided by the site l2beat.

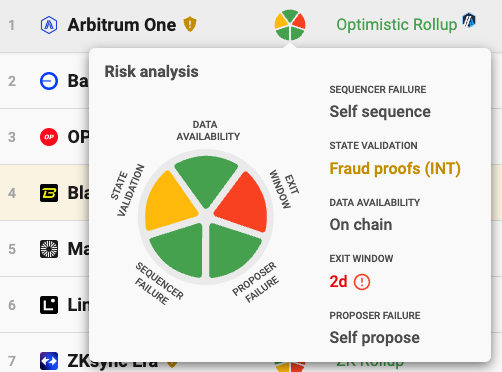

The risk profile is made up of 5 attributes that always answer a key criterion: Are I able to pull my funds out of the rollup at any time? This should be guaranteed even if part of the rollup infrastructure goes down.

- data availability

- exit window

- proposer failure

- sequencer failure

- state validation

Data availability: although some rollups use zero knowledge proof all transaction calldata must be available. For example in case of disaster calldata would be the only way to reconstruct the state from scratch. Keeping calldata in L1 is the safest way but too expensive.

Exit Window: an opinionated metric from those who created the metric, basically meets the requirement “Do users have at least 7 days to exit in case of unwanted upgrades”?

Proposer Failure: Proposer and Prover are basically the same role, except that in the case of optimistic rollup it does not generate evidence but only proposes the new block to put in L1. In case of proposer failure, the user can use a workaround (good) to withdraw funds from the rollup, generate a proof himself (good) or he can do nothing (not good) and wait for recovery.

Sequence Failure: as we have seen the sequencer is a bit of an entry point for transactions that are collected in batches. If this is broken we have two possibilities: there is a workaround that allows us to bypass the sequencer to act in L1 directly (good) or we can do nothing (not good) until it is restored.

State validation: means exactly what it says. Can it be verified that the block entered in L1 is valid? The zk-rollups do this by definition, the optimistic ones do not, they involve a challenge and fraud-proof protocol. In some rollups the challenge protocol can be launched by all users (good) in other cases there is a “manipulable” whitelist of users who can do the challenge (not good)

Rollups with more than $1b in capital are shown in the figure, but for brevity we limit ourselves to analyzing the data reported for Arbitrum and Optimism.

Analysis of Arbitrum according to the Stages framework.

According to l2beat.com Arbitrum is a Stage 1

It meets all the Stage 0 and Stage 1 requirements

- The project calls itself a rollup.

- L2 state roots are posted to Ethereum L1.

- Inputs for the state transition function are posted to L1.

- A source-available node exists that can recreate the state from L1 data.

Also.

- A complete and functional proof system is deployed.

- There are at least 5 external actors who can submit fraud proofs.

- Users are able to exit without the help of the permissioned operators.

- In case of an unwanted upgrade by actors more centralized than a Security Council, users have at least 7d to exit.

- The Security Council is properly set up

The problem that Stage 2 does not allow is that Arbitrum being an optimistic rollup has to implement a fraud proof mechanism, in the case of Arbitrum this mechanism is only enabled by a set of whitelisted actors and the whitelist is centrally governed. Clearly this means using a theoretically decentralized protocol in a “centralized” manner.

Also, upgrades to the protocol can be made effective in 3 days, given that at least 1 is needed for the exit transaction, it means giving only 2 effective days of exit window (remember that it should be at least 7).

Conclusions.

This article is in no way meant to be an attack on L2s such as Arbitrum, which, despite their current operational limitations, provide a valuable tool and even an interesting pilot case within the Ethereum ecosystem.

However, it must be clear to those who use them the difference between the safety and soundness of a transaction in L1 and what can happen in L2 that always represent a compromise. Then again, if this were not the case then Ethereum could itself implement the same architecture as a rollup and be more scalable than it actually is, but as we have seen, an L2 makes sense if there is an L1 that “supports” it.